It seems a foregone conclusion that we’re going to go with the “natural gas is a bridge fuel” logic, because it fits the current political narrative. I’d like to put this into perspective.

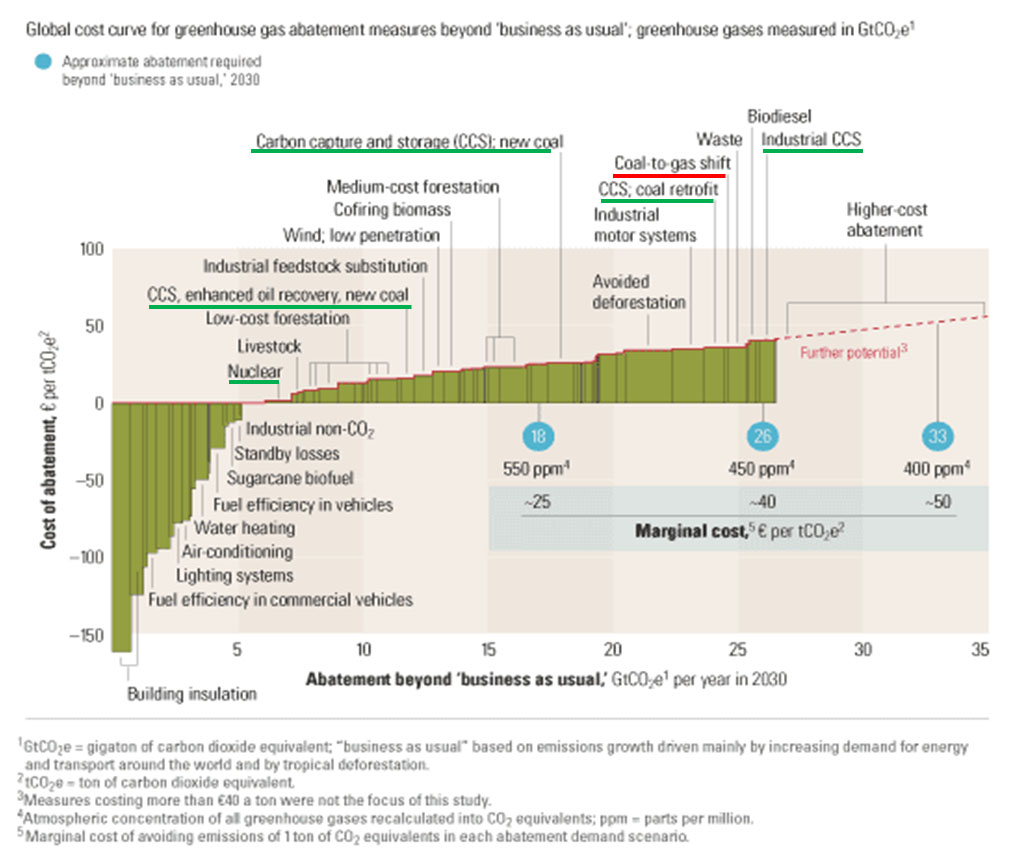

This approach puts us on the “Coal-to-gas shift” initiative, underlined in red, below:

Remember the McKinsey Cost Curve….right? Circa 2007! A little dated, but then again, not much has changed since 2007. I have always liked this representation, because it is simple.

The chart outlines a set of possible actions that could be deployed to reach a presumed 450 ppm atmospheric CO2 concentration target, the consensus, thought to be, threshold needed to limit the temperature increase to not more than 2°C.

The width of the bars in this stacked bar chart represents the magnitude of the contribution for each of these potential initiatives in GtCO2e (giga-tonnes of CO2 equivalent) per year in 2030. The height of each bar represents the cost, in euro, per tonne of CO2e. These defined actions are arranged by increasing cost. The negative cost actions on the left side of the chart are efficiency and conservation initiatives. Added cost initiatives are to the right.

There are two disturbing things about this chart:

- The first is how miniscule the positive effect of the Coal-to-gas shift is, underlined in red….

- And the second is how large the bars are for the Carbon Capture & Storage (CCS) and nuclear actions, seen as essential to reaching the 450 ppm target and underlined in green, and also the ones negatively affect by current policy.

The recent draft release of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report, Summary for Policymakers, concludes that there are very few options to reaching 450 ppm that don’t include CCS.

We need all of these actions, but right now, we have set the rules up so that we’re mostly getting the coal-to gasinitiative for new plants, compliments of the EPA and their supporting gas team. And, in that process we are killing the others. The rules have so distorted the competitive balance, that these other initiatives are no longer being pursued in any meaningful way.

I scaled these negative effects on CCS and nuclear and they are about times (25x) larger than that of the gains that could be realized from the coal-to-gas shift. OK, the Coal-to-gas shift will become larger as we build more Natural Gas Combined Cycle (NGCC) plants, but that contribution alone does not get us where we need to be.

The problem is in thinking that natural gas is the so-called “bridge”. Natural gas is the fuel. The “bridge” is CCS.CCS needs to be implemented across the board, and implemented without playing favorites. We also need to develop the full cost accounting tools to inform good policy decisions.

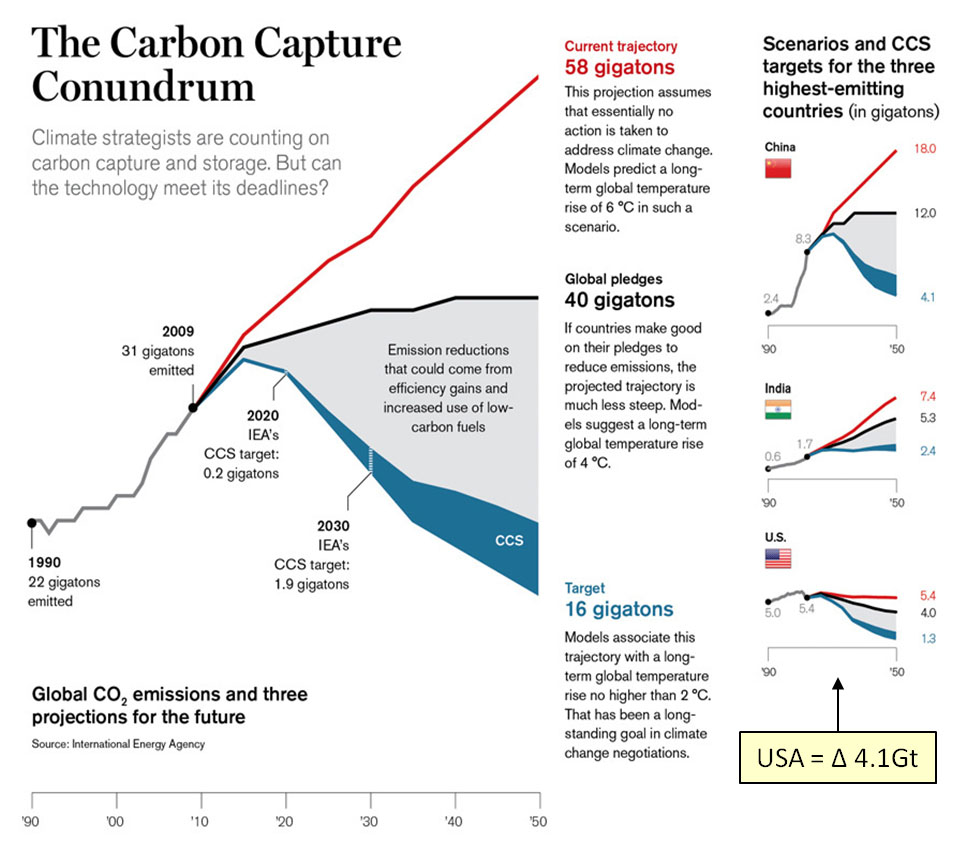

The Carbon Capture Conundrum, published by Mike Orcutt in 2012 offers another simplified explanation of the opportunity.The worldwide CO2 emissions are running at 31Gt /year and the consensus opinion is that the Business as Usual trajectory will reach 58 Gt by 2050, an increase of 27 Gt/year.

The Carbon Conundrum calls for a reduction of 42Gt in total from that Business as Usual trajectory with a U.S. contribution of a 4.10Gt reduction.

Mike Orcutt – M.I.T. Technology Review Aug. 2012

On June 2, 2014, the EPA released their draft ruling for CO2 emitted from existing power plants, referred to as the Clean Power Plan. It calls for a 30% reduction of CO2 from existing power plant sources, and is said to be complimentary with the previously announced NSPS for new power plants.

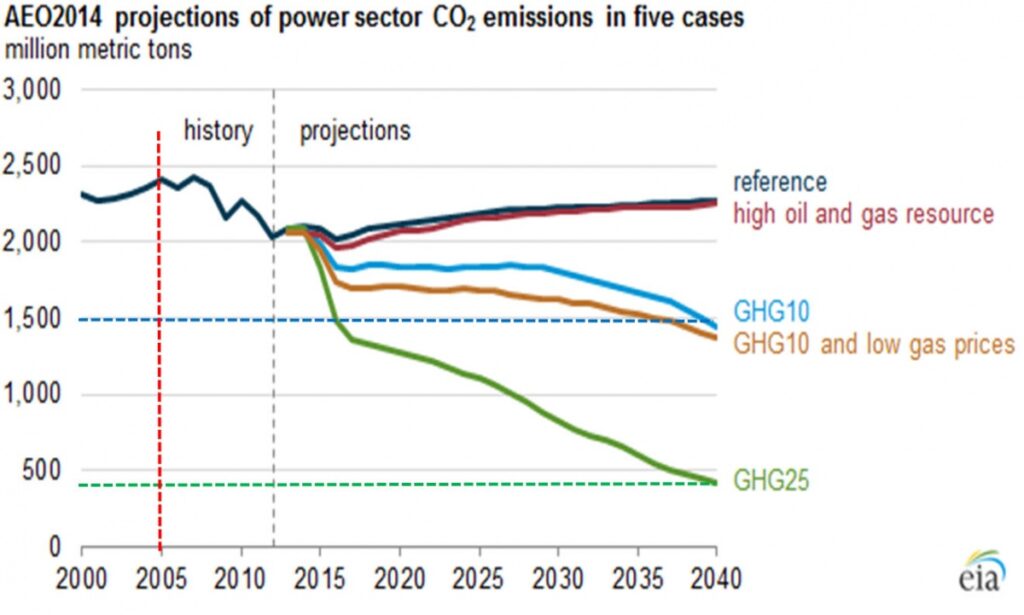

Coincidently, on June 9, 2014, the Energy Information Agency (EIA) also released a set of projections, as shown below.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Monthly Energy Review, September 2013, and the Annual Energy Outlook 2014

These EIA projections, as stated, do not specifically include the effect of EPA’s new ruling, but several scenarios explore the effect of a $10 and $25 Energy-Related CO2 fee, as well as fuel cost and availability differences.

The 2005 U.S. Power Sector CO2 emissions baseline for the new ruling is 2.40Gt (2400 million metric tonnes – red vertical line), or 40% of the 6.11Gt U.S. total, a number published elsewhere.The 30% reduction from this 2.4Gt level required by the Clean Power Plan is a target reduction of 0.72Gt. If this 0.72Gt represents that same 40% contribution, the overall U.S. reduction, assuming all sectors performed as well as the power sector, would be 1.80Gt vs. the 4.10Gt Carbon Conundrum target.

During the second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, the parties committed to reduce GHG emissions by at least 18 percent below 1990 levels in the eight-year period from 2013 to 2020. The 1990 U.S. CO2 emissions were 5.11Gt, of which 1.82Gt were from power plants. The resulting Kyoto targets (blue horizontal line) would then be 4.19Gt in total and 1.50Gt (1500 million metric tonnes) for power plants, assuming their same contribution…..the EIA GHG25 scenario at $25/tonne of CO2.

To achieve the overall reduction of 4.10Gt by 2040 with a 40% power-sector contribution rate, the U.S. power sector would need a 1.64Gt reduction and closer to 2.00Gt if the other sectors underperform. To achieve that 2.00Gt target reduction, the power sector would have to reach a 0.40Gt level (400 million metric tonnes – green horizontal line) and, per the EIA chart; this would imply some form of CO2 fee…. also on the EIA GHG25 trajectory.

In short, the EPA’s plan is a good start, but it is only a start.

It should be recognized that these ruling, while a good start, are at the same time, seriously undermining both nuclear and CCS initiatives.